By publishing the current entry on the Alphonsian Academy’s blog, we would like to draw your attention to the interesting reflections of the professors, graduates and also other persons connected with the Alphonsian Academy in Rome. To read more blog entries, please visit: http://www.alfonsiana.org/blog/

The Neighbor, Vulnerability and The Good Samaritan

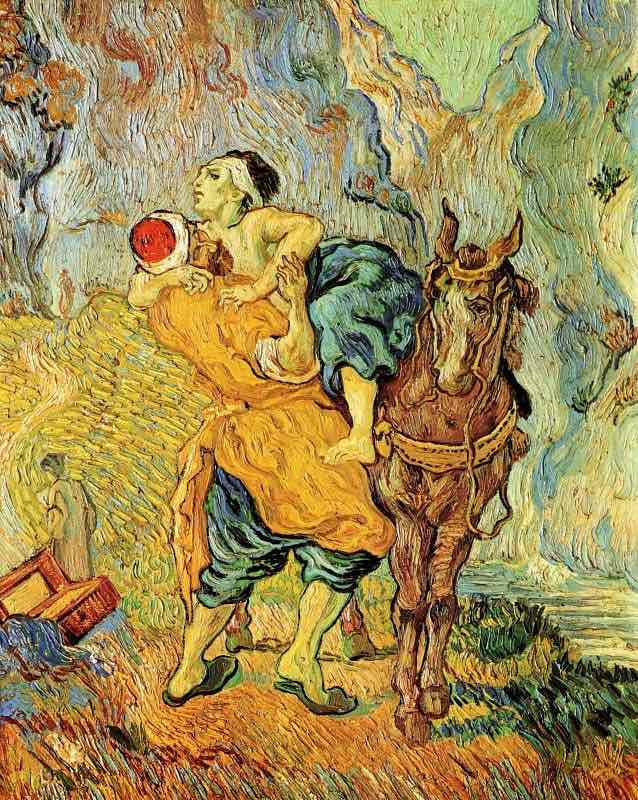

On September 27th I offered the Father of the Prodigal son for reflection as a model of capacious vulnerability. My comments on vulnerability last month might have surprised the reader who thinks of vulnerability primarily as the condition that raises alarm, concern, or the need to protect. I think of vulnerability, however, as that innate capacity we have to respond to the other who is at risk. Now I would like to take that insight further in a reflection on the Good Samaritan (Luke 10: 29-37).

It is important for us to remember why Jesus tells this parable. He has just given the commandment to love one another. In response, one of the Scribes asked Jesus, “Who is my neighbor?” A close reading of the story reveals that Jesus is offering a very surprising answer to the question.

At the beginning of the story we are thinking that the answer to the question “who is my neighbor?” is the man lying wounded on the road, that is, the precarious one. But by the end of the story we are no longer looking for the neighbor as the precarious one but at the vulnerable one who is acting. The Scribe rightly answers that the neighbor is the one who shows mercy.

In a similar way, when some read the Good Samaritan parable, they think of the wounded man as vulnerable, whereas others would think of the Good Samaritan as the one vulnerable to the condition of the precarious man. This inversion about vulnerability mirrors the inversion about the question of the neighbor itself. In a similar way the neighbor has gone from being object of concern to being responsive agent. The concept of vulnerability in contemporary literature has moved similarly from the wounded to the responsive.

Like the surprise ending, many of us forget that this parable was never primarily a moral one. Throughout the tradition many preachers and theologians saw in the story of the Good Samaritan the narrative (in miniature) of our redemption by Christ. Starting with Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150-ca.215), then Origen (ca. 184- ca.254), Ambrose (339-390) and finally, Augustine (354-430), the Good Samaritan parable is the merciful narrative of our redemption. Later from Venerable Bede (673–735) to Martin Luther (1483-1546), preachers and theologians appropriate and modify the narrative.

The basic allegorical expression of the parable was this: the man who lies on the road is Adam, wounded (by sin), suffering outside the gates of Eden. The priest and the Levite, (the law and the prophets), are unable to do anything for Adam; they are not vulnerable to him. Along comes the Good Samaritan (Christ), a foreigner, one not from here, who vulnerably tends to Adam’s wounds, takes him to the inn (the Church), gives a down payment of two denarii, (the two commandments of love), leaves him in the inn (the Church) and promises to return for him (the second coming) when he will pay in full for the redemption and take him with him into his kingdom.

The parable then is first and foremost not a moral story about how we should treat others, but rather the central story of our own redemption, that is, what Christ has done for us. We are called, if you will, to a mutual recognition, of seeing in Christ the one who became vulnerable for us so that we might be saved.

Like the Prodigal Son, the parable is about the scandal of our redemption, not how bad we are, but how vulnerable God in Jesus Christ is. In realizing how vulnerable God is, we recognize our own capacity for vulnerability, and therein discover the capacity and the call to go and do likewise.

Fr. James F. Keenan, SJ

About the author:

James F. Keenan, S.J., is Peter Canisius Chair, director of the Jesuit Institute and of the Gabelli Presidential Scholars Program at Boston College. Jesuit priest since 1982, he obtained his license and doctorate at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. He is an author or editor more than 20 books and over 400 contributions, articles and reviews. He is the founder of the Catholic Theological Ethics in the World Church (CTEWC) and chaired the First International Cross-cultural Conference for the Catholic Theological Ethicists, held in Padua in 2006, as well as the second international conference of moral theologians held in Trento in 2010.