Today, 23 May 2020, we have, for a few weeks or even months, been living in confinement such as we have never experienced before at a world level. Some countries are already experimenting with a “phase 2”, some people are experiencing the situation as being worse than that of the 1940s. 75 years after the end of World War II, “liberty” is acquiring a new meaning and great uncertainty about the future reigns everywhere.

“In 1812, around five hundred people with leprosy were locked up at Voorzorg, and in 1850 Batavia had 498 residents. Suriname had about 50,000 inhabitants in the first half of the 19th century, so, around one percent of the population was shut away in a leper colony. The Dutch historian Stephen Snelders calls this “the great confinement”. He sees a parallel to the mass separation of the mentally ill and beggars, homeless and other socially deprived people in Paris of the seventeenth century, described by the French historian/philosopher Michel Foucault and known as “le grand renfermement” (“the great lock-up”). The “(Omni)potent” state concludes that a certain part of the population is a danger to the rest of the population, and decides to exclude this group from society by separating them off into one or more institutions. In the Middle Ages it was the lepers in Europe. In the seventeenth century in France it was the mentally ill and others at the margins of society, the “lower social class”. And in the Dutch colony of Suriname, it was again from the eighteenth century that leprosy patients were locked away at the behest of those in power. […] In 1972 the last Surinamese leprosarium closed its doors. ” (H. Menke et al. De tenen van de leguaan. Verhalen uit de wereld van Surinaamse leprapatiënten, Volendam 2019, pp. 30-31).

In the past months almost all of us, ill from the virus, presumed ill from the virus, healthy, have experienced a “confinement”, often imposed by the State, more or less rigid confinement, of greater or lesser duration, alone or in the company of others, yet that in any case was or will only be temporary. For the lepers in Suriname, isolation meant until 1946: being locked away until death, because there was no cure for those actually suffering from leprosy. They had no hope of ever returning to a “normality” of any kind.

The confinement of the lepers was not just forced deportation. It also had even more serious consequences: it was a separation from family, it meant a poor diet: he who could no longer produce his own food depended on what the authorities gave him – and sometimes he had to fight to get a share of this because there wasn’t enough for everyone.

Taking care of the lepers was not seen as a duty, but was experienced as a punishment.

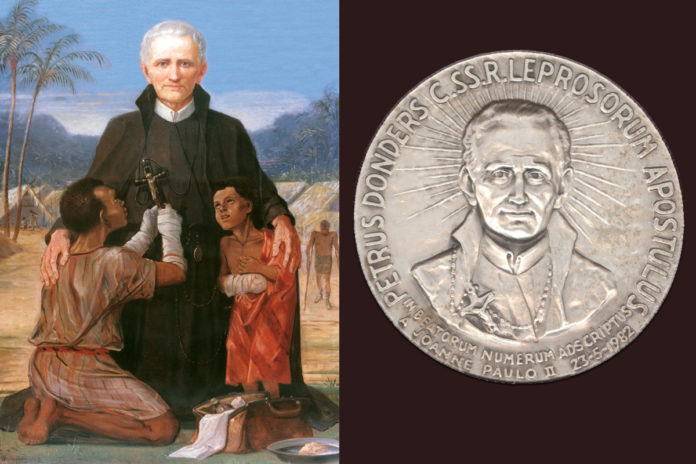

The blessed Peter Donders voluntarily shared the life of the lepers for 27 years – without being infected – at least during a paleopathological, and aDNA-based examination, finished in 2017, no infection was detected (for more information on the context of the study, see the above-mentioned book).

I have had to think of this often in the past few weeks. Peter Donders never longed for a return to a “normality”. And our “normality” will for a long time be a normality different from the normality of before 2020. In addition to the economy, “personal freedom”, “space”, “use of space”, but also “closeness” and “tenderness” need to be rethought. Longing for the normality of the past will be a utopia, and it is probably not desirable either.

I have had to think of this often in the past few weeks. Peter Donders never longed for a return to a “normality”. And our “normality” will for a long time be a normality different from the normality of before 2020. In addition to the economy, “personal freedom”, “space”, “use of space”, but also “closeness” and “tenderness” need to be rethought. Longing for the normality of the past will be a utopia, and it is probably not desirable either.

Mgr. Karel Choennie, the Bishop of Paramaribo, has taken as the starting point for his sermon on Good Friday, titled The COVID-19-cross, the drawing reproduced here at the right.

Today, on the anniversary of the beatification of Petrus Donders, we can keep in mind that the confinement imposed on us is temporary, we have a future, the great majority of those infected will recover – despite the lack of medicine, but often thanks to the effort of medical personnel.

May the example of the blessed Peter Donders inspire us not merely to hope for a better future, but to practice moderation, restraint, to limit ourselves a little, voluntarily, where necessary and desirable, and that when we are allowed to leave our rooms again, we will have actually reflected and have changed – for the sake of the health of others as well as ours, to prevent a second wave of the pandemic, for the sake of a new, more equable and better sustainable future!

For a touching article about Petrus Donders see https://stclemens.org/docs/A macule on the back.pdf.

Claudia Peters, vice-postulator Causae Petri Donders C.Ss.R., vicepostulator@peerkedonders.nl