by Rogério Gomes, C.Ss.R.[1]

Introduction

On March 27th, 2020, the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life published the document, Gift of Fidelity and the Joy of Perseverance, Guidelines.[2] The text, within its limitations, touches on a recurrent and troubling problem in Consecrated Life, the perseverance of the members. In 3 parts: 1) looking and listening, 2) rekindling self-knowledge, and 3) separation from the Institute (canonical norms and the practice of the dicastery), the document presents some causes of defection, as well as some considerations and proposals to assist the reflection on the problem. Therefore, if the dicastery produces such a document, it is because the phenomenon affects the Church in general and wants to contribute a reflection on this reality that also touches us as a Congregation.

- Some theories that shed light on this reality

The problem of crisis and perseverance is not one that only affects Consecrated Life. It influences the post-modern human being in his personal choices and especially traditional institutions: family, Church, school, and politics. Various philosophical, psychological, and sociological theories seek to explain the reality of today’s world from multiple points of view. The metaphors “the illusion of the end”, the “simulacrum”[3], “pluralism and the crisis of meaning”[4], “the society of the spectacle, of the tiredness and the transparency”[5], “the society of individuals and self-consciousness”[6], the “era of emptiness, of the ephemeral, of the twilight of duty”[7], of the “weak thought”[8] and the liquid: “liquid modernity, liquid love, liquid life, liquid fear, liquid times, liquid art and life in fragments”[9] are attempts to understand the fragmented world in which we live.

What we are experiencing is, in fact, is a crisis of personal, collective, and institutional identity. Who am I? How do I relate? What do I expect from institutions? Faced with the impact of social and technological change, the individual has to reinvent himself at every moment, and there is no time to mature his options. In a way, the context itself forces him to do so, and it becomes a question of mimetics and survival. To cite an example: in the past, a person entered the world of the workforce, accumulated experiences, created relational links with other colleagues, had certain stability, and formed his family in the context of his work. Often his children ended up choosing their parents’ profession because of certain identification. In today’s context, in addition to the requirements of experience, competence, and updating, durability in the workplace is very short (in the interest of the system), and, to survive, the subject has to position himself in other jobs, taking away from time spent living with his peers: family, friends, and the possibility to think about fundamental choices, in order to mature them. In this sense, the current situation, with all of its advances, favors superficiality since the individual is attached to a web of relationships so complex and guided by speed and efficiency that while he matures chronologically, he can remain immature at the level of fundamental and lasting options.

Some years ago, Giuseppe Tacconi researched various authors who try to explain the crisis in Religious Life. He warned that all readings of the crisis have their limits and cannot give an answer in themselves. They should be read together and with a mentality and attitude of openness. He distinguishes six interpretations:

1.Ethical interpretation, because of the crisis of values in society and the indifference to the Gospel and religion.

Religious life as an affirmation of the preeminence of God and, as a consequence, becomes impractical and impossible. Added to that is the loss of the radicality of Consecrated Life, and its becoming secularized and less spiritual;

- Sociological interpretations, the displacement suffered by Religious Life in the social and ecclesial context.

With the significant social transformations, especially those Congregations with very specialized social works, Religious Life loses its social relevance. This loss is due to the new realities of assistance such as caritas and new models of churches with greater participation of the laity, of NGOs, of volunteers and also because Religious Life adopts a logic separated from society and does not utilize networks.

The Church context provokes a marginalization of Consecrated Life that many times by accepting so many parishes, Consecrated Life becomes a supplement of the diocesan clergy and also a security guarantee for itself. The decline in the number of vocations and the aging of the members places the apostolates in crisis. Very old communities with few young members do not offer room for change because control is in the hands of the elders. Another element is the influence of transformations in gender relations within religious life as religious women move to demand greater equality within the Church. The difficulty of managing the passage from a model of Religious Life that is positioned in a relatively homogeneous context of Christianity to a model in an ever more complex and secular context is a challenge.

- Psychological interpretations, the problem of self-realization, and the conflicts between self-realization and community life that generate disillusionment and crisis.

The lack of realism in living a loss of contact with concrete reality, the experience of time, and a manic hyperactivism that often hides anguish, dissatisfaction, and pessimism. The fragility in the decision processes that are slow, fragile, and always postponed, without confrontation and of projecting results in time and space; the problem of self-reference, the difficulty of getting out of oneself and the impoverishment of relationships; the inertia, routine, and accommodation of what exists; the crisis of identity as Religious persons. The “how” of being a Religious person is known, but not the “why” of this identity. This crisis is not only that of individuals but also of a collective identity. This crisis challenges Religious to shift from a movement of simplification to that of complexity, with new dynamics and synthesis and to bring together the different identities that they live as men and women, Christians, religious, citizens, and professionals.

- Historical interpretations, the transition between a past that no longer exists, and a new one that is not yet envisioned.

This does not mean the end of Consecrated Life. To survive in time, many forms of Religious Life changed over time; many disappeared, others were born. To progress, it is necessary to renounce a deadly fixism. It is essential to have the memory of the past to live the present time more consciously.

- Theological interpretations:

Some authors insist that the crisis is a lack of deepening in the theology of Consecrated Life and the difficulty of passing from a static theological model to a dynamic-evolutionary model, capable of entering into dialogue with contemporary culture. Others insist on the loss of the foundational reference, Jesus Christ, and the emergence of an ecclesial model that passed from the centrality in Jesus to social practice. Others present the crisis as a descent, weakness, loss of the significance of participation in the cross of Christ.

- Pragmatic interpretations: Consecrated Life was built on the model of Consecration and Mission (the being for). Secularized society has put in crisis the forms, mediations, and instruments that were developed in different historical contexts that today no longer respond to the challenges. The inability of Religious Life to communicate ad intra and ad extra, the lack of global projects, and the post-conciliar renewal did not reach everyone and remained a model of the past. Self-criticism was not an element reflected in the elaboration of new models; it was demolished without development[10].

That being so, theoretical reflections are essential to understand the phenomenon in a comprehensive manner. However, we can run the risk of seeing it only as a sociological phenomenon caused by the current situation that arrives in our communities, affects us, and we continue to follow life as spectators. “The reality of defections in Consecrated Life is a symptom of a wider crisis that questions the various forms of life recognized by the Church. This situation cannot be justified only by citing socio-cultural causes or by confronting the resignation that leads to considering it as normal. It is not normal that after a long period of initial formation or after long years of Consecrated Life to decide to ask for a separation from the Institute”[11]. This may be the time to touch our wounds and, without looking for culprits, take history into our hands and in an earnest, mature, responsible, restless, hopeful way and with faith in the Lord of the Harvest and Shepherd of the Flock, think about and address this reality in our communities. It is not a question of seeing reality from the perspective of pessimism, but of the realism and the search for better solutions to respond to a real problem.

- A look at our reality

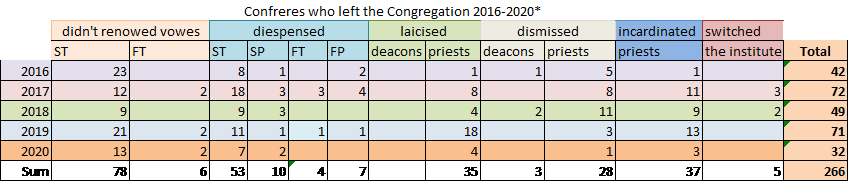

In recent times, a large number of confreres, some very young, have left the Congregation in various situations, requesting a leave of absence and exclaustration, and also, passage to a diocese.[12] From 2016 to the present time, analyzing the documentation that comes to the General Council concerning absences, exclaustration, expulsion, leaves of absence, and serious crimes, we have the following data that should lead us to a sincere reflection without choosing scapegoats.

* Legend: Data as of 31 August 2020 ST - Students (clerics) in temporary vows FT - Brothers in temporary vows SP - Students (clerics) in perpetual vows FP - Brothers in perpetual vows

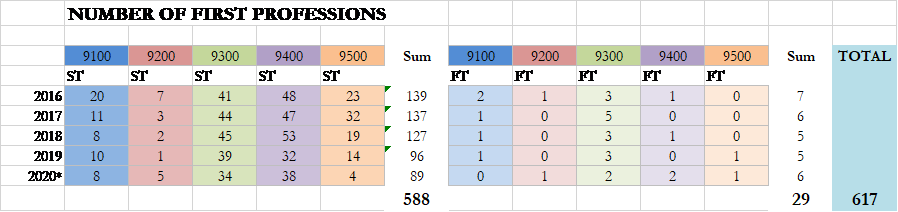

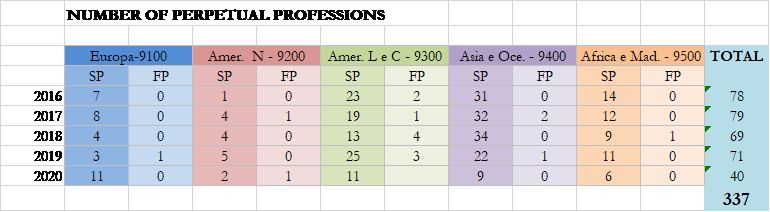

Faced with this phenomenon, the question we must ask is: what can we do as an institution (leadership, formation) to strengthen perseverance in the Congregation? Analyzing the number of young men who enter our seminaries, we see a high reduction in the number of first professions, decreasing numerically for Perpetual Profession and ordination. What is happening? Although the data are approximations, since they consider a time frame (2015-2020), and not precisely, the entire period from the first profession to the perpetual profession for each Conference, even so, the reduction is evident. Moreover, among the number of departures, the inevitable phenomenon of deaths must be considered. From 2016 to August 31st, 2020, 499 confreres died in the whole Congregation. If we consider both the departures and deaths, we have a number diminishment of 765 confreres. To be constituted as a Province, a Unit must have 50 members. The number of Provinces then is equivalent to 15. This means the loss of evangelizing strength. The number of perpetual professions, 337, does not replace the number of departures and deaths. More detailed data can be obtained from the different archives of the Congregation Conferences.

What happens to the confreres who confront the reality of disenchantment with the style of life and the mission, pastoral models no longer attractive to the confreres and to the People of God, the lack of consistent formation that has not led them to discernment before perpetual profession, the difficulty in dedicating a whole life to an ongoing project, the absence of spiritual life, community life that does not offer companionable and affective support, the lack of resilience in the working through community conflicts and the facing of difficulties, the incompatibility of the Congregational charism with personal gifts, the passage of many to Diocesan life and other Institutes? These are points that should be reflected upon and discussed in our religious communities.

Analyzing the responses received from the Congregation’s [Vice] Provinces in preparation for the XXVI Chapter, it can be seen that one of the most fragile aspects is linked to initial formation and, even more so, to continuing formation. Formation for Consecrated Life is entrusted, in most cases, to the novitiate as a panacea and a time of apprenticeship, especially for the contents related to Consecrated Life. Subsequently, attention is strongly focused on ministerial formation (doing) at the expense of Consecration (being). How can quality initial formation be guaranteed if there is no personal and community investment in ongoing formation? Another focus of tension and fatigue is community life. On the one hand, there is communitarianism that stifles individuality, that watches over others’ lives, authoritarianism, and on the other hand, there is almost a “diocesanization” and the weakening of the missionary body in which the individual is alienated from everything and everyone. How can we reconcile personal values and charisms to balance the experience of our apostolic life and be a resource to strengthen fidelity and perseverance? How can the process of restructuring help us with this?

- Fidelity and the vow and oath of perseverance (Const. 76)

The word fidelity (fidelitas-atis) has both a theological and anthropological content. Fidelity is linked to the act of faith in oneself, in God, and in the other (person and institution). That is, the observance of the faith “giving-to”. The faithful (fĭdēlis, derived from fides) is he who observes the faith given, which corresponds to the trust in the one in whom the faith has been placed. Therefore, it is a reciprocal act. In this sense, it is fundamental to ask ourselves if the causes of the abandonment of the Institute are not linked to a crisis of faith: faith in God, in the Consecration itself, the mission, and its recipients. When a person consciously and courageously discerns to leave, it is because he does not any longer find meaning in his Consecration. The opposite is true and can be a problem both for the Institute and for the People of God.

Faced with the problem of perseverance in the early days of the Congregation, Alphonsus instituted the vow and oath of perseverance. This fourth vow is a way of counteracting the current view of the transience and liquidity of commitments, especially those that require people to commit their lives to another or an institution. In this sense, the vow of perseverance is a sign to the world that it is possible to make lifelong commitments to those who have no one on their side. In this case, we commit ourselves to the explicit proclamation of the Good News and the Kingdom, and for this, we devote our lives.

To persevere is not to hold out in time chronologically until death. A confrere can have many years in Redemptorist life and is not be persevering. There may be only a formal adherence to the institution as a form of survival and not a lifelong commitment to the mission. Perseverance entails the whole being with its weaknesses and strengths and the willingness to give the best of oneself.

The vow of perseverance has as its essence Christ, who persevered in his mission until the end, giving his life on the cross. It goes beyond the daily routine through creative fidelity and conforms the person more and more to the mission of Jesus himself and the Congregation. Only in this way does it make sense “[…] the vow and oath of perseverance, by virtue of which they oblige themselves to live in the Congregation until death (Const. 76).

Conclusion: to reflect as a missionary body

Reflecting on this complex issue that affects not only Consecrated Life, but also marriages, friendships, and the labor world, we realize that the answers are neither obvious nor magical. The answers are the result of a birth experience that we must face together as a missionary body. Perhaps some indications can help us be more aware and start thinking concretely about strategies to optimize this situation. Below are some elements:

Understanding the cause of abandonment.

Each (V)Provincial Government and each formation house has an idea of the factors that led the person to leave his way of life. It is important to discern what are the difficulties / the (dis)motivations of the individual and also the incapacity of the institution in helping him. A coherent analysis is also willing to make an institutional self-evaluation.

Investing human and financial resources in the pastoral care of vocations.

There are realities in the Congregation where there are young people, but the (V) Provinces do not invest in confreres to free them for this missionary work. It is necessary to provide confreres who have a feeling for the work with young people or at least allow themselves to be guided into doing a good job. Today, more than publicizing the charism, it is necessary to understand who is the young person, his world, his wounds, his qualities, and his openness to make a lasting commitment. A vocation ministry that seeks out perfect young people is condemned to failure. In this sense, restructuring can offer significant possibilities of human and economic resources and solidarity.

More participatory and discernment-oriented formation programs.

The challenge of forming people today is enormous, and it is not an easy task. Dealing with people all the time, talking, listening, offering content, helping to discern is exhausting, and a job that is not seen with the naked eye. In the past, formation was a mass production: one entered the formation house, participated in the study program, lived the discipline, professed, and was ordained. Today, there is a double task, since the formator has to work with the formand in a personalized way and then return him to the broader context of the community and work with him from there. The present generations bring new questions to the formators that past generations did not have. Besides the personal and community work of the formators, it is important to rethink the ways of planning formation programs. Imposing a program in the formation house decided by the Secretariat of Formation without involving the formandi in the preparation can be less laborious, but less effective. To involve the young people in the formation process is to believe in them and to make them subjects of the formation process, since they can give their opinion, bring their concerns about the world, about sexuality, and the affectivity components that need attention. How, then, can we reconcile the contents of formation which cannot be renounced, so that young people can give their opinions making them and their opinions important and the program more attractive? This requires a dialogical formative process, which listens, focuses on reality, on discernment, and prompts young people to more difficult tasks, while taking them out of passivity and opening the world for them (Const. 20).

Reconciling missionary charism and personal gifts (self-realization).

Throughout the formation process, the person must discern that the congregational charism persists in time, adapts, renews itself with the breath of the Spirit, and reads the signs of the times, but does not adapt itself to persons. Otherwise, it would not respond to its mission in the Church. The Congregation’s charism is not to take care of hospitals or education, which means that if the young person has this charism, he must be helped to find his way consciously and accompanied with joy because he has found his true direction. However, this does not mean that, at a given moment, the major superiors, because of a necessity and a project that responds to the needs of the charism, do not entrust to the confrere a formation in medicine or education or other areas. It is important that those in leadership have a vision and a broad knowledge of the confreres and seek to reconcile pastoral work with personal gifts, which is a challenge to help the formandi in their self-realization. The protagonists are often characterized by rigidity in negotiating the charism and personal gifts. Different is the selfish protagonism in which the individual makes his own life and identifies himself as the mission (la mission c’est moi). The confrere who understands the service of the Congregation puts his personal gifts to use and fulfills himself without departing from the missionary body.

Awareness of continuous formation.

We must be humble and recognize that one of the deficiencies we have in the Congregation is continuing formation. In the context of today’s world, basic formation in philosophy and theology is very little. It requires constant updating on our part, and a continual updating of the awareness and interest that each one of us should have in keeping up with the challenges of the world, and seeking the means to open different horizons to the themes that are presented to us daily. It is not about specialized formation. This is only one aspect of continuing formation. It is about processing information into knowledge (knowing, reflecting, meditating, praying) to be useful for life and mission.

Ongoing formation is not just about filling us with content. It also has its spiritual and mystical dimensions. In general, the (V) Provinces offer annually a time of formation for the confreres that is not always appreciated. The lack of continuing formation causes us to give old answers to new problems. This accommodates and leads us to love the pastoral work of maintenance. The continuing formation will not give us all the answers, but it does teach us that, if we do not have it, qualitatively listening is already a great answer. To disregard continuing formation is, at minimum, a sin against poverty! If we want quality initial formation, we must be aware that continuing formation is fundamental not only for the formators, but also for each confrere.

Work on personal and group resilience.

One of the weak points of our initial and continuous training process is the work of resilience and conflict resolution. In general, we are not trained for this. Most of the time, a simple problem that could have been resolved at its genesis through dialogue and understanding branches out and becomes more complex, generating a series of damaging personal and community consequences. Conflict is anthropological. However, it goes through an educational process, learning and focusing energies towards the common good. Currently, couching consultants have successfully worked on this issue in work environments, families, etc. Considering this reality in formation houses and religious communities can be a learning experience and also a significant contribution to the quality of community life.

This present text has its limitations, especially as it may not respond to all the situations that are presented. However, we must discuss all of this openly and clearly in our communities, without fear, without pessimism, without prejudice, without accusations, and without indifference. Fidelity is an act filled with faith, perseverance, patience, the desire to do one’s best, and to love God, the Congregation, and God’s People. Fidelity helps us to touch wounds with courage and serenity, as surgeons, who to heal have to have the courage to open bodies, deal with pain, be persistent, accompany, and care.

Liquid perseverance in a fragmented world raises many concerns and should not discourage us. As a missionary body, we have to take our story into our hands as a story of Redemption. “The first witness we give to the Redeemer as consecrated religious is to read and grasp our own personal story as a story of Abundant Redemption”[13]. In this story of redemption is present the memories of our journey, “The Way”, the discouragements, the weaknesses, the failures, the crosses, the fidelities and infidelities, the desire to do it well, and the daily resurrections that help us to persevere. To assume the story of Redemption is also to assume the story of those who left and of those who continue with the desire to respond to the questions of the Spirit, which always reflect the true source of our charism.

[1] http://lattes.cnpq.br/3342824164751325

[2] Cf. The CONGREGATION FOR INSTITUTES OF CONSECRATED LIFE AND SOCIETIES OF APOSTOLIC LIFE. The gift of fidelity. The joy of perseverance. Città del Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2020..

[3] Cf. BAUDRILLARD, Jean. La ilusión del fin. La huelga de los acontecimientos. Barcelona: Anagrama, 1995; BAUDRILLARD, Jean. Cultura y simulacro. Barcelona: Kairós, 1998.

[4] Cf. BERGER, Peter; LUCKMANN, Thomas. Modernidad, pluralismo y crisis de sentido. La orientación del hombre moderno. Barcelona: Paidós, 1997.

[5] Cf. DEBORD, Guy, La sociedad del espectáculo. Valencia: Editorial Pre-textos, 1999; HAN, Byung-Chul. La sociedad del cansancio. 2ªed. Barcelona: Herder, 2017; VATTIMO, Gianni (1994). La sociedad transparente. Barcelona: Paidós, 1994.

[6] Cf. ELIAS, Norbert. The Society of Individuals, by Norbert Elias. New York: Continuum, 2001.

[7] Cf. LIPOVETSKY, Gilles. La era del vacío. Barcelona, Anagrama: 1986; LIPOVETSKY, Gilles. El crepúsculo del deber. La ética indolora de los nuevos tiempos democráticos, Anagrama. Colección Argumentos: Barcelona, 1996; LIPOVETSKY, Gilles, El imperio de lo efímero. Madrid: Editorial Anagrama, 1990.

[8] Cf. VATTIMO, Gianni; ROVATTI, Pier Aldo. Il pensiero debole. Milano: Feltrinelli, 2010.

[9] Cf. BAUMAN, Zygmunt. Modernidade líquida. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2000; Amor líquido: sobre a fragilidade dos laços humanos. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2003; Vidas desperdiçadas. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2004; Vida líquida. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2005; Medo líquido. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2006; Tempos líquidos. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2006; Arte, ¿líquido?. Madrid: Ediciones Sequitur, 2007; Vida em fragmentos: Sobre ética pós-moderna. Zahar, 2011.

[10] Cf. TACCONI, Giuseppe. Alla ricerca di nuove identità: formazione e organizzazione nelle comunità religiose di vita apostolica attiva nel tempo della crisi. Leumann (Torino): Elledici, 2001, p. 35-57.

[11] CONGREGACIÓN PARA LOS INSTITUTOS DE VIDA CONSAGRADA Y LAS SOCIEDADES DE VIDA APOSTÓLICA. El don de la fidelidad. La alegría de la perseverancia, n.5.

[12] Cf. Communicanda 2/2019, n. 108.

[13] Communicanda 1 (2017), n. 2.