Advent meditation with Saint Alphonsus and Pope Francis

“The invitation to joy is characteristic of the Advent season: the wait for the birth of Jesus, the wait we live is joyful, a bit like when we wait for a visit from someone we love very much, for example, a friend we haven’t seen for a long time, a relative… We are in joyful expectation” [1].

…therefore, not a passive but an active expectation, because it is patient and constant (cf. IIa reading of the Third Sunday of Advent; 1Ts 5,16-24) like that of the Baptist “who – except Our Lady and Saint Joseph – was the first and most experienced the expectation of the Messiah and the joy of seeing him come (cf. Jn 1,6-8.19-28)”[2].

Is it you… or do we have to wait for another one

O God, who calls the humble and the poor to enter your kingdom of peace, make your justice spring up among us,

that we may live in joy as we await the coming of the Savior.

(Third Sunday

Collect)

A “healthy” wait

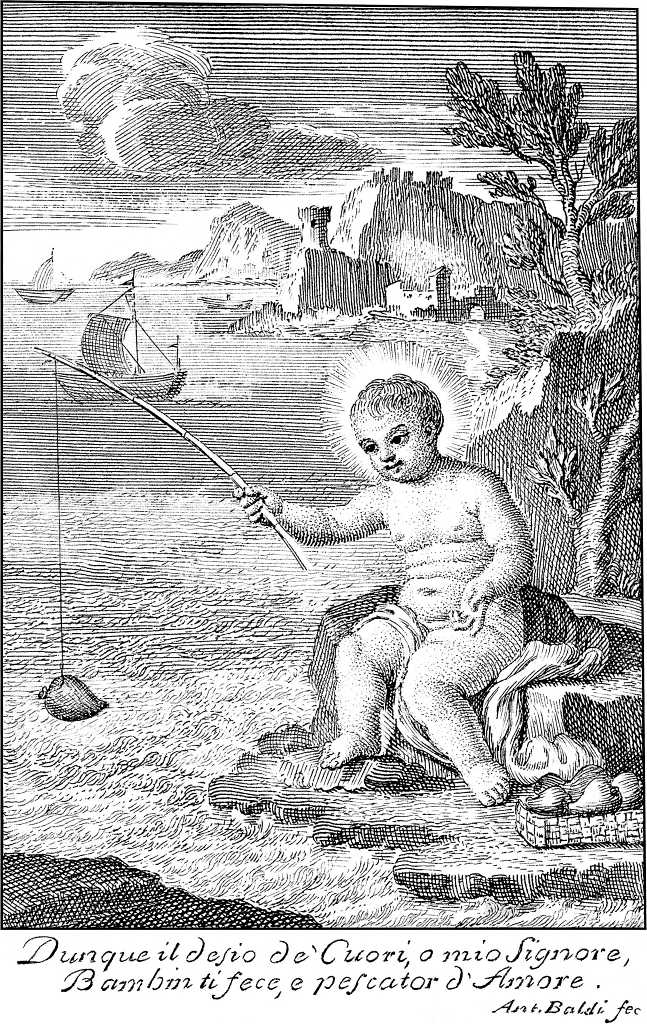

In his fourth Advent meditation, Saint Alphonsus offers an interpretation that we might say is “salutary” – in the eminently Alphonsian sense – of the “waiting” for the Redeemer for which humanity has been called to prepare itself. God the Father – writes de Liguori – “allowed four thousand years to pass after Adam’s sin before sending his Son to earth to redeem the world”. In this we are called to admire “the divine wisdom; she postpones the coming of the Redeemer to make it more pleasing to men: she postpones it so that the evil of sin, the necessity of the remedy and the grace of the Savior may be better known. If Jesus Christ had come immediately after Adam’s sin, the greatness of the benefit would have been underestimated[3]. With his advent – we read in the sixth meditation – the world has been freed both from the darkness of idolatry, because with his person, Christ, “gives the light of the true God”, and from the darkness of sin, through the “light of his doctrine and his divine examples[4].

The restlessness that moves the search… and the action of God

In Alfonso’s writing, the restlessness that animates the expectation and active search of the Baptist – and perhaps also the heart of every man – seems to find an answer on the lips of the eternal Father, to whom Alfonso makes “say”: “This poor child […] that you see, O men, laid in a manger of beasts and stretched out on straw, know that this is my beloved Son who has come to take upon himself your sins and your pains; love him, therefore, for he is too worthy of your love and too much he has obliged you to love him” [5]. Certainly the “salvation of all men” nothing “could add you” to the greatness of God, yet “he did and suffered so much to save us wretches”[6]. Only “a God was capable of loving us miserable sinners with such excess since we were so unworthy of being loved[7].

A verb that recurs several times in the texts of the holy Doctor, it is the verb “to seek” applied yes to man but much more to God. In the ninth meditation, for example, it is Christ himself who sets out to seek man, thus fulfilling the words of the prophet Isaiah (Is 35:1-6a.10). “I am a poor sinner,” writes Alphonsus, and then turning to the beloved Redeemer he exclaims, “but these sinners you said you came to seek: ‘For I did not come to call the righteous, but sinners’ (Mt 9:13). I am a poor sick man, but these sick you came to heal, saying: “It is not the healthy, who need a doctor, but the sick” (Lk 5:31). I am lost for my sins, but you have come to save the lost“[8].

Further on, as a personal resolution to the previous discourse, Alphonsus writes: “My Jesus […] You have come from heaven to seek the lost sheep. Seek me, therefore, and I seek none other than you”[9]. You “have said that whoever opens you should not be afraid to enter you and stay in your company (Rev 3, 20). If at one time I drove you away from me, now I love you, and I desire nothing but your grace. Behold, the door is open, enter my poor heart, but enter it never to leave again. He is poor, but by entering you will make him rich. I will be rich, as long as I possess you, my greatest good[10].

…more food for thought

Ah my dear Child, tell me what you have come to do in this land? Tell me who are you looking for? I already know, you have come to die for me, to free me from hell. You have come to seek me, a lost sheep, so that I may no longer flee from you and love you. (Cf. Nine Meditations for Each Day of the Novena, 267).

You do not know how to abandon a soul that seeks you; if in the past I left you, now I seek you and love you (cf. Ibid. , 273)

Fr. Antonio Donato, C.Ss.R.

(see the original text in Italian)

[1] Francis, Angelus, St. Peter’s Square, 12/13/2020.

[2] Ibid.

[3] A. M. de Liguori, [Meditations] Per li giorni dell’Avvento sino alla novena della nascita di Gesù Cristo, in Opere ascetiche, IV: Incarnazione – Eucaristia – Sacro Cuore di Gesù, Redentoristi, Rome 1939, med. IV, 147-148; [= Advent].

[4] Ibid. , med. VI, 152.

[5] Ibid. , med. VII, 155. Concerning the inner obligation to love the one who first loved, Alphonsus writes in his fifteenth meditation: placed in front of the “excess of goodness and love [of] a God [who has] willed to reduce himself to appear as a little child, clasped in swaddling clothes, placed on straw, crying, trembling with cold, unable to move, needing milk to live, how is it possible not [to feel] pulled and sweetly compelled to give all his affections to this infant God who has reduced himself to such a state in order to make himself loved?». Certainly “if without faith we enter the cave of Bethlehem, we will have nothing but an affection of compassion in seeing a child reduced to such a poor state, that being born in the heart of winter is placed to lie in a manger of beasts, without fire and in the middle of a cold cave”. If, on the other hand, we enter with a lively faith, like the shepherds “who were enlightened by faith”, we will recognize “in that child the excess of divine love, and by this love inflamed [we will] go on praising and glorifying God” (cf. Ibid. , med. XV, 173-174).

[6] Cf. Advent, med., IX, 158.

[7] Ibid. , med. IX, 158. In the thirteenth meditation Alphonsus takes up this concept and, addressing the reader, says: “Consider how Jesus suffered from the first moment of his life, and he suffered everything for our sake. Throughout his life, he had no other interest after the glory of God than our salvation. He, as the Son of God, did not need to suffer to merit paradise; whatever He suffered in suffering, poverty, and ignominy, He applied it all to merit our eternal health. Indeed, being able to save us without suffering, he wanted to take on a life of pain, poor, despised and abandoned by every relief, with a death the most desolate and bitter that has ever made any martyr or penitent, to make us understand the greatness of the love that brought us and to earn our affections. He lived […] to obtain for us divine grace and eternal glory, to have us always with him in paradise” (Ibid. , med. XIII, 168-169).

[8] Advent, med. IX, 159.

[9] Ibid. , med. X, 162.

[10] Ibid. , med. XII, 168.