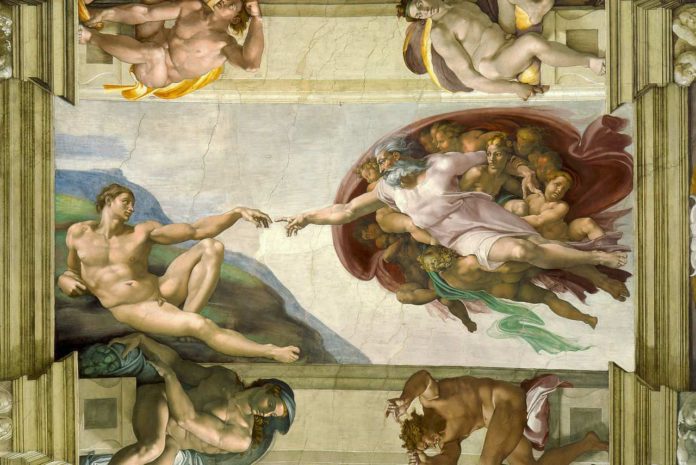

When we think of being in the image of God we might think of the Sistine Chapel where the figure of Adam on the ceiling just about to be awakened by the touch of God bears an identical image of the Judge and the Lord of the Resurrection on the back wall. Michelangelo’s Adam bears the face of Christ, the Alpha and Omega. We, Adam, are in the image of the one who has conquered sin and death.

But there is another, more original, let’s call it “vulnerable” image that connects the creation of Adam with the birth of Jesus.

In the twenty-first chapter of T.H. White’s wonderful The Once and Future King (Ace Books, New York 1987), we read a memorable account of creation. On the fifth and sixth days of creation, God gathers all the embryos of each and every species of animal life and offers each embryo a wish for something extra. The giraffe embryo gets a long neck for tree food, the porcupine asks for quills for protection, and so it goes for the entire animal kingdom. At the end of the entire ordeal, the last embryo is the human who when asked by God what he wants, responds: «I think that You made me in the shape which I now have for reasons best known to Yourselves, and that it would be rude to change… I will stay a defenceless embryo all my life». God is delighted and lets the human embryo have no particular protection, to be the most vulnerable of all newborns and says: «As for you, Man… You will look like an embryo till they bury you».

White’s vision of the human embryo as the bearer of human vulnerability is remarkable, for behind this decision is the assumption that we are made in God’s image and that if we are vulnerable, so is God. And so White concludes his account with God disclosing to the human, “Adam”: «Eternally undeveloped, you will always remain potential in Our image, able to see some of Our sorrows and to feel some of Our joys. We are partly sorry for you, Adam, but partly hopeful».

I think that what God saw in Adam at that moment is not unlike what Mary and Joseph see in the birth of the child Jesus. In fact, it is what the shepherds saw and what the wise ones travelled to see? The remarkable tendency of Christianity is that we celebrate the birth of God made flesh and the Gospels of Luke and Matthew insist on giving us the details inviting us to see and consider what they did.

The birth of Jesus is indeed vulnerable. Mary and Joseph are in search of a place where they are not known, and their only accommodation will be a precarious stable. Jesus will not be surrounded by relatives from far and wide, but rather by farm animals and their herders.

Still, it’s a capacious vulnerability, like White’s birth of Adam. The child is received by an inn keeper, a foster father, a group of sheep herders and some wise men from afar. Each recognize in the child what Mary was promised, Emmanuel, God is with us.

We are invited on Christmas to see what they saw, God in the infant Jesus and there encounter a mutual recognition where we see the ineffability of God expressed in a new born child in a manger. There we are beckoned to see ourselves as we really are, in his image, that is ours.

In the vulnerable child we see our vulnerable selves. Let us not betray the revelation.

What is the mystery that we encounter but that same mystery that all found in the vulnerable flesh of a newborn, the God of all creation. But let us see in that revelation how dependent on each other we are, in that vulnerability where we are most like God.

And so, like those in the story, let us now be still as we attend to him!

Fr. James F. Keenan, SJ