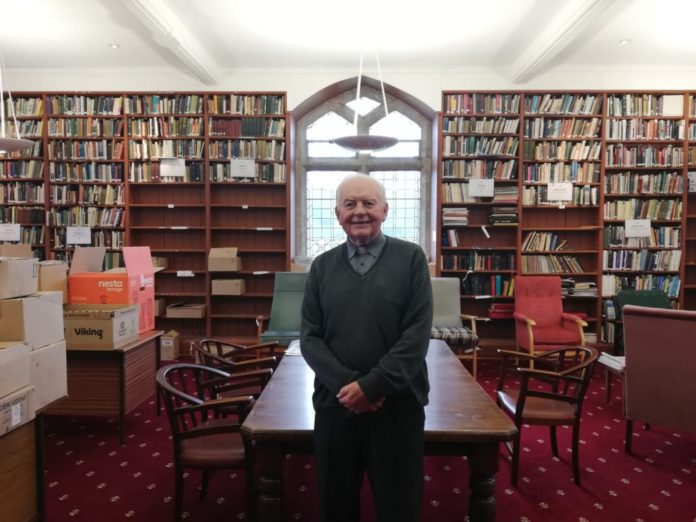

Redemptorist Father John Hanna in the library of Clonard Monastery in Belfast, Northern Ireland, which hosted the peace talks leading to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. (Credit: Claire Giangravè.)

BELFAST – Tucked between two worlds, the Clonard Monastery in West Belfast remains a symbol of dialogue and encounter in post-conflict Northern Ireland. Not only is it placed between notoriously tough Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods, but it was the setting for peace talks that would eventually lead to the historic Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

The Redemptionsist church, built in 1911, played a crucial role in promoting dialogue between Republican, Nationalist Catholics and Loyalist, Unionist Protestants, and continues to bring the communities together for Mass and prayer.

Still, pushed up against the walls that run though the city separating Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods, it’s difficult to ignore the violent past that enveloped the church for years.

“The Berlin wall is gone, but ours is still here,” Father John Henna, one of the 14 Redemptionist priests serving at the monastery, told Crux while overlooking the mighty fences.

The church is no stranger to violent riots and shootings since it endured the bombings during the global conflicts of the last century and offered asylum to the community. After 1969, when political and religious tensions reached their climax and the walls were erected, the area surrounding the monastery could have been compared to a battleground.

In the bloody period that followed, known as “The Troubles,” the monastery became key to the region’s peace process.

Hanna said the church played that role in large part because of the visionary leadership of two of his fellow Redemptorists, both based at Clonard: Father Alec Reid, who died in 2013, and Father Gerry Reynolds, who passed away two years later in 2015.

Reynolds was an ecumenical pioneer, and it’s said that he visited more Protestant churches in his lifetime than any priest in the history of Ireland.

He once said that the “destiny of Christians in Northern Ireland is to help make an end of the Reformation conflict. For the Catholic congregations the promised land is among their Protestant brothers and sisters; for the Protestant congregations it is among their Catholic brothers and sisters.”

Reid, meanwhile, began his efforts as a peacemaker during the mid-1970s during visits to Irish nationalists in British prisons, where he tried to reconcile the moderate and radical wings of the movement.

From 1987 to 1998, Reid encouraged conversations between John Hume, leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), and Gerry Adams, who was the Leader of the nationalist party Sinn Féin until last February.

Those historic talks, as well as those with the British government and interfaith conversations, all took place within the brick-covered monastery, a safe-haven from the turmoil outside.

“It became a sanctuary place where people could come and talk,” Hanna explained.

He was living there at the time and served coffee, tea and cakes to the “interesting people” who would drop by, from members of the British army to IRA members. The meetings between Hume and Adams were meant to be secret, he said, and they came in through separate doors, “but there are no secrets here.”

Hanna described the mood in the room, which held the destiny of Northern Ireland, to be good during the talks, and said there was much hope that lasting peace might emerge.

One day, as he passed by a printer upstairs, he saw a secret copy of the long-awaited agreement abandoned by the machine.

“I could have made a killing off of it!” he quipped, but instead he said he destroyed it and newspapers the next day, Aug. 31, 1994, announced “the complete cessation of military operations” by the IRA.

Reid lived long enough to see the coronation of his efforts, which led to the historic 1998 Good Friday Agreements and the formation of a joint unionist and nationalist government, and later even moved on to negotiating peace between Basque separatists and the Spanish government.

Hanna was transferred from Clonard to Cork, Ireland, in 1998, and only returned two years ago. Twenty years later, he said Belfast is a different place than he remembers, where cheer and hospitality is more its trademark than sectarian feuds.

The city he came back to is “certainly peaceful,” he said. “It has become a tourist attraction!” he added.

The graffiti-covered walls that once symbolized hatred and division have now become a favorite spot for foreign visitors, and black taxis carry tourists though the city to get the Nationalist, Unionist sight-seeing tour.

Hanna said Belfast has changed in other ways too, with a diminishing sense of community and an increase in interfaith marriages between Catholics and Protestants.

Though he admits that these continue to be “difficult times,” he says religion continues to play an important role.

“Church is very popular, the people still come,” he said.

In 1981, the Clonard Monastery twinned with Fitzroy Presbyterian Church at Queen’s University, carrying the torch of dialogue. Every Thursday the monastery holds novenas, which draws up to 15,000 people – strikingly, including good numbers of Protestants who also stay for Mass.

Clonard also broadcasts the novenas online, with up to 5,000 people tuning in to listen, and has even launched its own app.

Faithful from Clonard will also be attending the World Meeting of Families Aug. 21-26 in Dublin. Hanna dismissed any idea that people in Northern Ireland were disappointed because the pope isn’t visiting them.

“It’s a media thing,” he said, but reported that many are looking forward to the upcoming papal visit. “There is excitement about it, there is enthusiasm,” Hanna said, before adding with a smile, “it’s going to be interesting.”

(cruxnow.com, Claire Giangravè, Aug 16, 2018)